Offshore Magazine

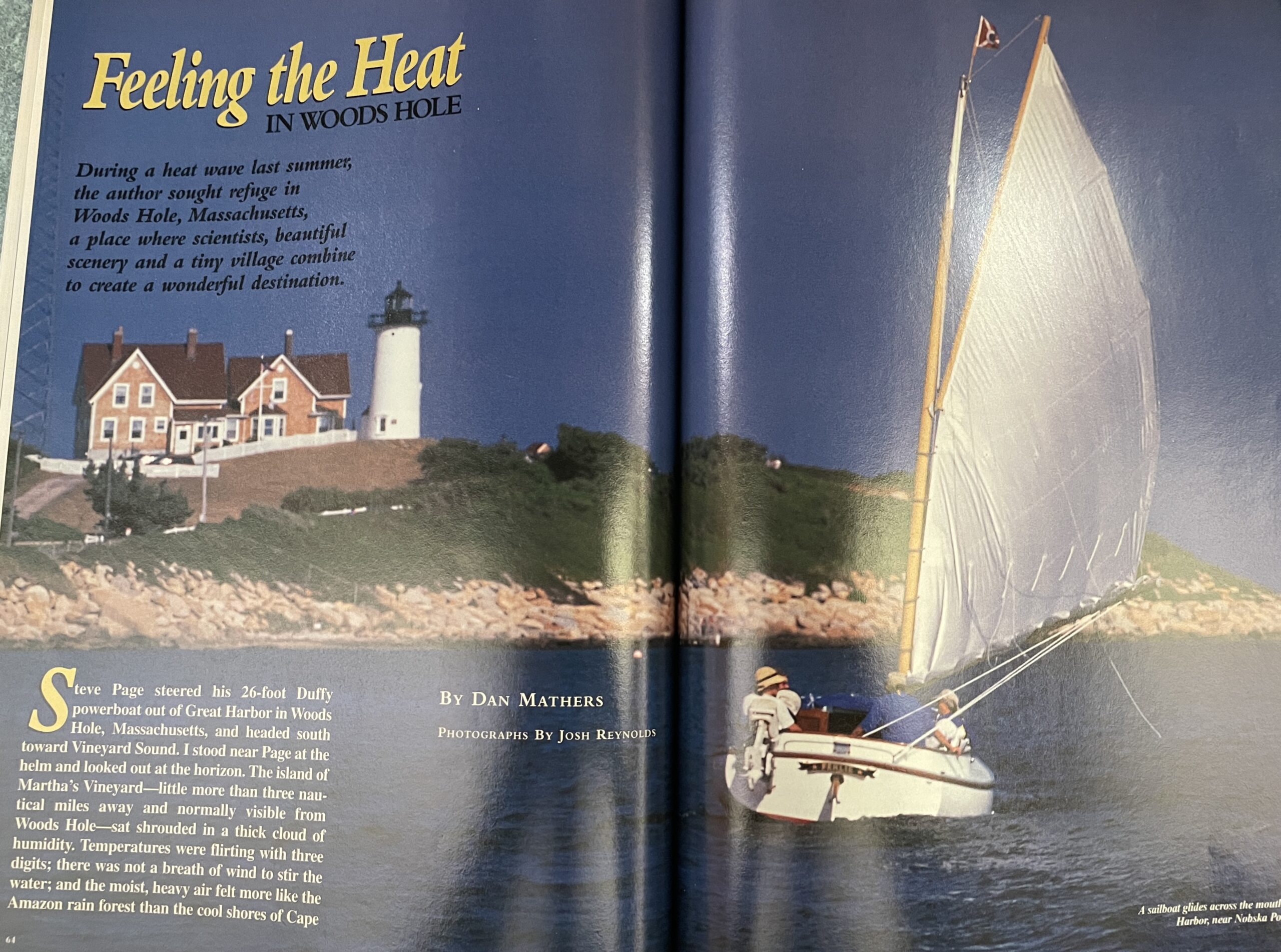

Feeling the Heat in Woods Hole

During a heat wave last summer, the author sought refuge in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, a place where scientists, beautiful scenery and a tiny village combine to create a wonderful destination.

(Text below)

Steve Page steered his 26-foot Duffy powerboat out of Great Harbor in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and headed south toward Vineyard Sound. I stood near Page at the helm and looked out at the horizon. The island of Martha’s Vineyard—little more than three nautical miles away and normally visible from Woods Hole—sat shrouded in a thick cloud of humidity. Temperatures were flirting with three digits; there was not a breath of wind to stir the water; and the moist, heavy air felt more like the Amazon rainforest than the cool shores of Cape Cod. Being on the water gave me no relief from the heat, and I was not happy about it.

That morning—the hottest day of a week-long heat wave last August—I had sat in an air-conditioned living room planning to spend the day in the cool indoors watching Jerry Springer and Hogan’s Heroes reruns. It was not to be. My wife Becky had visions of us doing something outside. It was crazy talk as far as I was concerned, and I attributed it to her being four months pregnant. Then she reminded me that, come winter, I’d wish for hot days like this. She had a point. I hate winter.

We figured it would be cool by the water, and friends of ours suggested we check out Woods Hole, a pretty little village at the southwestern end of Cape Cod. With popular shops, restaurants and renowned scientific institutions, Woods Hole has a college-town-meets-fishing-village atmosphere. It is the kind of place where you can take in beautiful scenery, shop, learn about marine science, and enjoy a great meal all in a day. Becky and I had never been to Woods Hole, and it sounded like fun.

Our friends gave us the name of a charterboat captain they knew, Steve Page, who could take us for a cruise of the scenic waters around Woods Hole. We met Steve at his boat, Obadiah, docked along Great Harbor. With his long, gray beard and soft-spoken manner, Steve seemed every bit the part of a Cape Cod salt. He recently retired from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, where he worked on shipboard electronics. Now he spends his days operating his charterboat and fishing. His 19-year-old son, Elisha, came with us as we motored out onto the water.

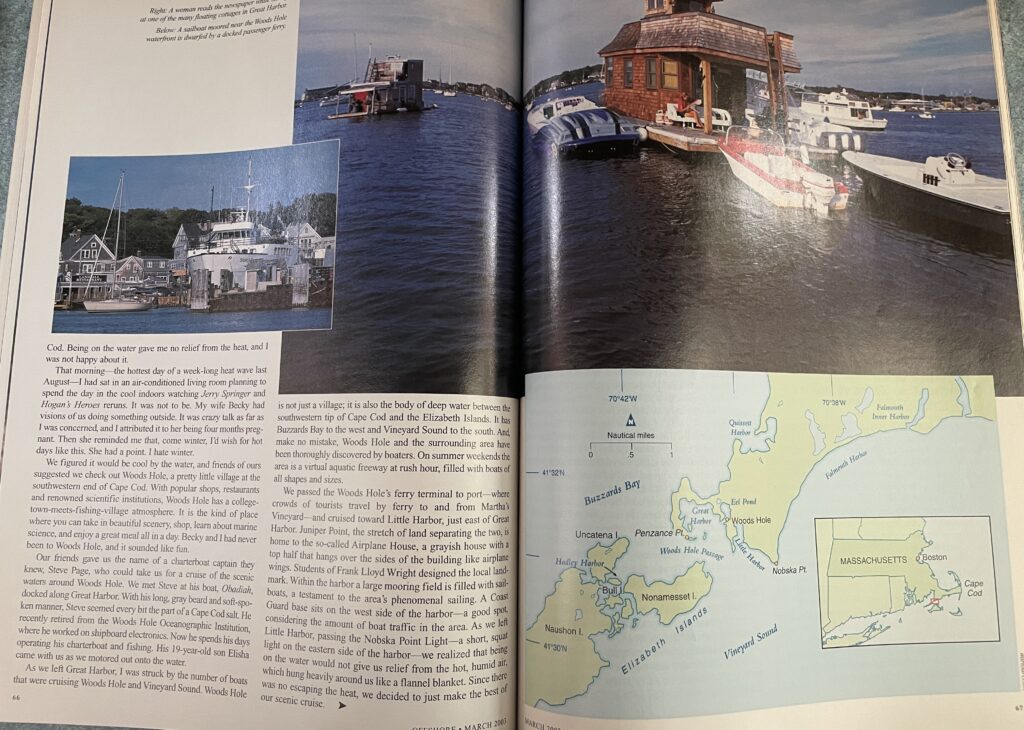

As we left Great Harbor, I was struck by the number of boats that were cruising Woods Hole and Vineyard Sound. Woods Hole is not just a village; it is also the body of deep water between the southwestern tip of Cape Cod and the Elizabeth Islands. It has Buzzards Bay to the west and Vineyard Sound to the south. And, make no mistake, Woods Hole and the surrounding area have been thoroughly discovered by boaters. On summer weekends the area is a virtual aquatic freeway at rush hour, filled with boats of all shapes and sizes.

We passed the Woods Hole’s ferry terminal to port—where crowds of tourists travel by ferry to and from Martha’s Vineyard—and cruised toward Little Harbor, just east of Great Harbor. Juniper Point, the stretch of land separating the two, is home to the so-called Airplane House, a grayish house with a top half that hangs over the sides of the building like airplane wings. Students of Frank Lloyd Wright designed the local landmark. Within the harbor a large mooring field is filled with sailboats, a testament to the area’s phenomenal sailing. A Coast Guard base sits on the west side of the harbor—a good spot considering the amount of boat traffic in the area. As we left Little Harbor, passing the Nobska Point Light—a short, squat light on the eastern side of the harbor—we realized that being on the water would not give us relief from the hot, humid air which hung heavily around us like a flannel blanket. Since there was no escaping the heat, we decided to just make the best of our scenic cruise.

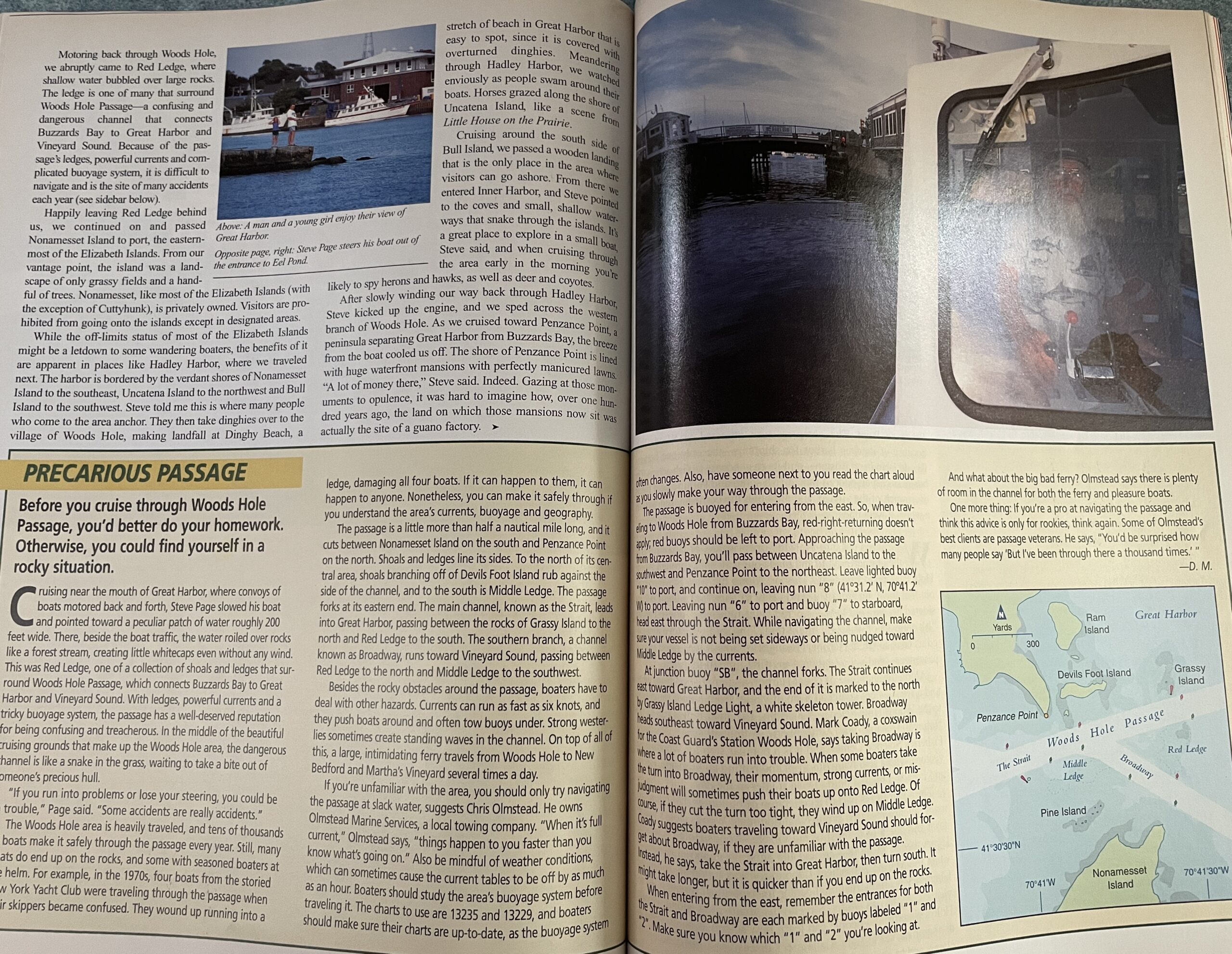

Motoring back through Woods Hole, we abruptly came to Red Ledge, where shallow water bubbled over large rocks. The ledge is one of many that surround Woods Hole Passage—a confusing and dangerous channel that connects Buzzards Bay to Great Harbor and Vineyard Sound. Because of the passage’s ledges, powerful currents and complicated buoyage system, it is difficult to navigate and is the site of many accidents each year.

Happily leaving Red Ledge behind us, we continued on and passed Nonamesset Island to port, the easternmost of the Elizabeth Islands. From our vantage point, the island was a landscape of only grassy fields and a handful of trees. Nonamesset, like most of the Elizabeth Islands (with the exception of Cuttyhunk), is privately owned. Visitors are prohibited from going onto the islands except in designated areas.

While the off-limits status of most of the Elizabeth Islands might be a letdown to some wandering boaters, the benefits of it are apparent in places like Hadley Harbor, where we traveled next. The harbor is bordered by the verdant shores of Nonamesset Island to the southeast, Uncatena Island to the northwest and Bull Island to the southwest. Steve told me this is where many people who come to the area anchor. They then take dinghies over to the village of Woods Hole, making landfall at Dinghy Beach, a stretch of beach in Great Harbor that is easy to spot, since it is covered with overturned dinghies. Meandering through Hadley Harbor, we watched enviously as people swam around their boats. Horses grazed along the shore of Uncatena Island, like a scene from Little House on the Prairie.

Cruising around the south side of Bull Island, we passed a wooden landing that is the only place in the area where visitors can go ashore. From there we entered Inner Harbor, and Steve pointed to the coves and small, shallow waterways that snake through the islands. It’s a great place to explore in a small boat, Steve said, and when cruising through the area early in the morning you’re likely to spy herons and hawks, as well as deer and coyotes.

After slowly winding our way back through Hadley Harbor, Steve kicked up the engine, and we sped across the western branch of Woods Hole. As we cruised toward Penzance Point, a peninsula separating Great Harbor from Buzzards Bay, the breeze from the boat cooled us off. The shore of Penzance Point is lined with huge waterfront mansions with perfectly manicured lawns. “A lot of money there,” Steve said. Indeed. Gazing at those monuments of opulence, it was hard to imagine how, over one hundred years ago, the land on which those mansions now sit was actually the site of a guano factory.

In 1863, the Pacific Guano Works set up its fertilizer plant on Penzance Point. The company was attracted to Woods Hole because of its deep harbor for shipping—the only one between Rhode Island and Boston—and its easy access to fish scraps. The business cast on odor of rancid fish scrap and sulfuric acid fumes over much of the village, and although the company did well for a while, it went under in 1889.

We cruised out into the wide-open waters of Buzzards Bay, then turned around and made our way back through Woods Hole Passage toward Great Harbor. Along the way, Steve pointed out that traveling from Buzzards Bay to Vineyard Sound is considered heading out to sea, so ‘red-right-returning’ doesn’t apply. “It’s opposite of what you might think,” he said. As Steve navigated us back to Great Harbor, I thought of how it was good to be a passenger—and not a captain—my first time in this area.

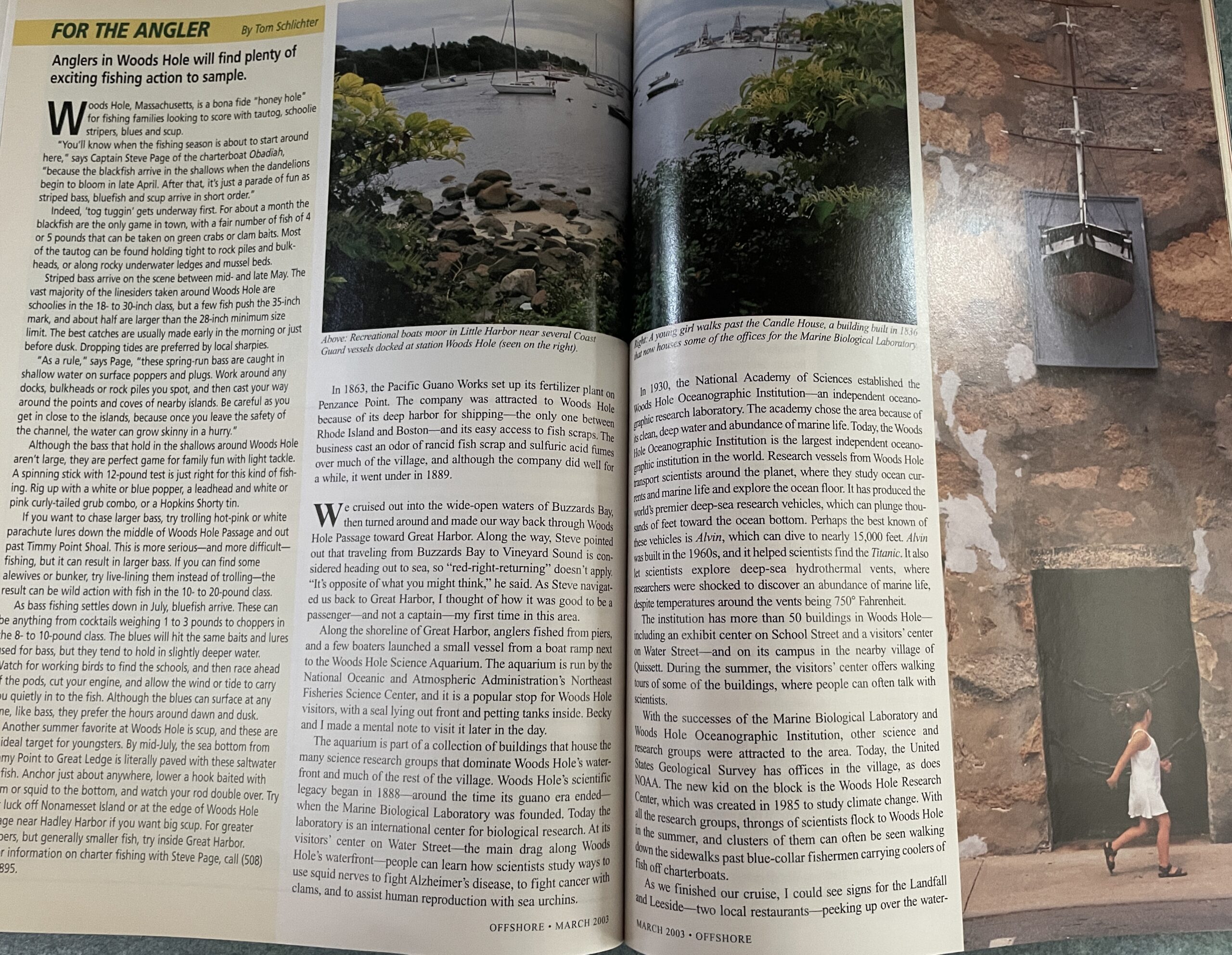

Along the shoreline of Great Harbor, anglers fished from piers, and a few boaters launched a small vessel from a boat ramp next to the Woods Hole Science Aquarium. The aquarium is run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center, and it is a popular stop for Woods Hole visitors, with a seal lying out front and petting tanks inside. Becky and I made a mental note to visit it later in the day.

The aquarium is part of a collection of buildings that house the many science research groups that dominate Woods Hole’s waterfront and much of the rest of the village. Woods Hole’s scientific legacy began in 1888—around the time its guano era ended—when the Marine Biological Laboratory was founded. Today the laboratory is an international center for biological research. At its visitors’ center on Water Street—the main drag along Woods Hole’s waterfront—people can learn how scientists study ways to use squid nerves to fight Alzheimer’s disease, to fight cancer with clams, and to assist human reproduction with sea urchins.

In 1930, the National Academy of Sciences established the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution—an independent oceanographic research laboratory. The academy chose the area because of its clean, deep water and abundance of marine life. Today, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is the largest independent oceanographic institution in the world. Research vessels from Woods Hole transport scientists around the planet, where they study ocean currents and marine life and explore the ocean floor. It has produced the world’s premier deep-sea research vehicles, which can plunge thousands of feet toward the ocean bottom. Perhaps the best known of these vehicles is Alvin, which can dive to nearly 15,000 feet. Alvin was built in the 1960s, and it helped scientists find the Titanic. It also let scientists explore deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where researchers were shocked to discover an abundance of marine life, despite temperatures around the vents being 750° Fahrenheit.

The institution has more than 50 buildings in Woods Hole—including an exhibit center on School Street and a visitors’ center on Water Street—and on its campus in the nearby village of Quissett. During the summer, the visitors’ center offers walking tours of some of the buildings, where people can often talk with scientists.

With the successes of the Marine Biological Laboratory and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, other science and research groups were attracted to the area. Today, the United States Geological Survey has offices in the village, as does NOAA. The new kid on the block is the Woods Hole Research Center, which was created in 1985 to study climate change. With all the research groups, throngs of scientists flock to Woods Hole in the summer, and clusters of them can often be seen walking down the sidewalks past blue collar fishermen carrying coolers of fish off charterboats.

As we finished our cruise. I could see signs for the Landfall and Leeside—two local restaurants—peaking up over the walerfront. They made me hungry, and since I hadn’t found any relief from the heat out on the water, I thought maybe an ice-cold beverage would do the trick. We did Steve and Elisha Page adieu as they dropped us off onshore. Then they headed back out to check their lobster pots, and Becky and I walked off to see if we could find something tasty ourselves.

In the village, crowds of people walked along the sidewalks carrying backpacks and pushing baby strollers. They wove in and out of the visitors’ centers, gift shops, clothing stores and restaurants. All along Water Street, bulletins were posted on walls and telephone poles advertising poetry readings, chamber music concerts, theater productions and yoga classes. Clearly, Woods Hole had plenty of activities to keep both scientists and tourists busy.

Woods Hole has scores of great restaurants to choose from, and our mouths watered as Becky and I inspected menus. Ultimately, though, it wasn’t menus but my affection for pirate themes that won out, and we decided to have lunch at the Captain Kidd. Inside the Kidd, tabletops sat atop on wooden barrels, and small barrels were used as seats. Ships’ wheels and life rings hung from the wall opposite a long, wooden bar with a bountiful beer selection. Indoors, out of the sun, the air actually felt nice. But when the hostess asked where we’d like to sit, I stupidly answered, “Outside, please.”

We sat under an umbrella on the restaurant’s deck, and it gave us shade and some relief from the heat, but it was still hot. I coveted the idea of cooling off with a tasty margarita. But my pregnant wife would have fed me to the seagulls for sipping one in front of her. She loves margaritas, too. In fact, we joked about naming our daughter Margaret Rita. Well, to my wife it was a joke. Becky ended up enjoying an alcohol-free pina colada, while I cooled off with an ice-cold beer. Thankfully, Becky hates beer.

The deck reached out onto Eel Pond, which extends into the village like a teardrop from Great Harbor. The pond is home to scores of moored boats, which enter the pond by passing under the Water Street bascule bridge. Every half-hour during summer days, the bridge opens to let boats pass through, stopping the heavy pedestrian traffic along the street.

As Becky and I ate, we watched the action on the water. Eight female mallards swam around the deck battling two nasty seagulls for the food diners occasionally threw into the water. Once, while the feathered beasts weren’t paying attention, two large stripers swam up to snag a few bites. The sight of the stripers in the clear pond water caused an excited stir among customers. “No wonder there are people fishing off the docks,” Becky commented.

After lunch, we walked down to the aquarium at the end of Water Street. The aquantum—which has free admission—had information on the marine life found in local waters. Its tanks held some of those local fish, such as stripers, dogfish and Atlantic cod, as well as a few colorful

species found in the tropics. We walked up to the aquarium’s second floor, where we looked down into the tops of the first floor’s tanks. We watched as the fish skimmed the top of the water. A small shark’s fin cut the surface, like a miniature Jaws. Groups of children gathered around “touch tanks,” where they held horseshoe crabs, starfish and other marine life. Nearby, an octopus climbed up the glass wall of its tank; then, upon reaching the top, he spread out his eight tentacles like a parachute and floated to the bottom, where he proceeded to climb back up and do it again.

After leaving the aquarium, we walked back up Water Street. There was plenty left to see and do in Woods Hole—tour the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s exhibit center, go shopping, visit the Woods Hole Art Gallery—but the heat had sapped our energy, and we were ready to cozy up to our air conditioner. So much for finding relief by the water, I thought.

As we walked, we passed a waterfront park that looked out onto Great Harbor. It was a beautiful view, and Becky and I sat on a bench to enjoy it. The few bits of sunlight that cut through the haze glistened on the water. Powerboats cruised through the harbor, and we could see a few tall sailboats in the sound. The green fields of Nonamesset Island looked bright against the gray haze.

As we got ready to walk on, a strong breeze blew in off the water, cooling us like a fan.

“Oh, that feels nice,” Becky said.

“See,” I said, “I told you it would be cooler by the water.”