Offshore Magazine

Plymouth Pilgrimage

Nearly 400 years after the Pilgrims settled here, visitors are still discovering the charm of Plymouth, Massachusetts.

(Text below)

Facing starboard in my little yellow boat, I adjusted my cap and leaned forward. The tiny wavelets of Plymouth Harbor reflected the white summer sun like a mirror, and I squinted to study the coastline, scanning from left to right and back again.

“No Pilgrims yet,” I muttered to myself.

Four hundred years ago, Plymouth, Massachusetts, was a frightening, primitive, untamed wilderness. Today, this oldest of the old New England towns is a happy, busy tourist mecca that exudes history.

For two days, I’d been exploring the town, visiting museums, going on tours, talking with the locals and learning about the town’s history and its famous founders. Now, I was out on the water trying to visualize an earlier time.

I’d known the story of the Pilgrims and the first Thanksgiving since grade school, but the struggle and hardship they endured were never more real to me than when I was sitting in that boat, thinking about an image I’d seen on a souvenir place mat. It was a painting of the Mayflower arriving in Plymouth on a miserable December day, surrounded by a frigid sea and a foreign wilderness. The scene was so desperate and grim, so different from my cartoon-influenced perception of the Pilgrim experience, I couldn’t get it out of my mind.

And so, obsessed with this image, I rented a 16-foot aluminum skiff at the town wharf and went out to the same spot where the Mayflower was pictured. My boat had no name, only the number “9” painted in red along the sides. As the tiny outboard struggled to push it along, the hull of the 9 shook and hummed, and my feet and legs vibrated to the beat of the engine.

I took the 9 out to the middle of the harbor, the engine screaming all the way. Behind me, boats zipped along the coast of Plymouth Beach, a 2 ½-mile sandbar that cradles the harbor like a mother’s arm. To my right, people water-skied. To my left, they fished. A tour boat passed in front of me. Humanity and civilization were everywhere. Again, I tipped my cap low on my forehead, leaned forward and squinted hard toward the coast, trying to imagine what the Pilgrims must have seen.

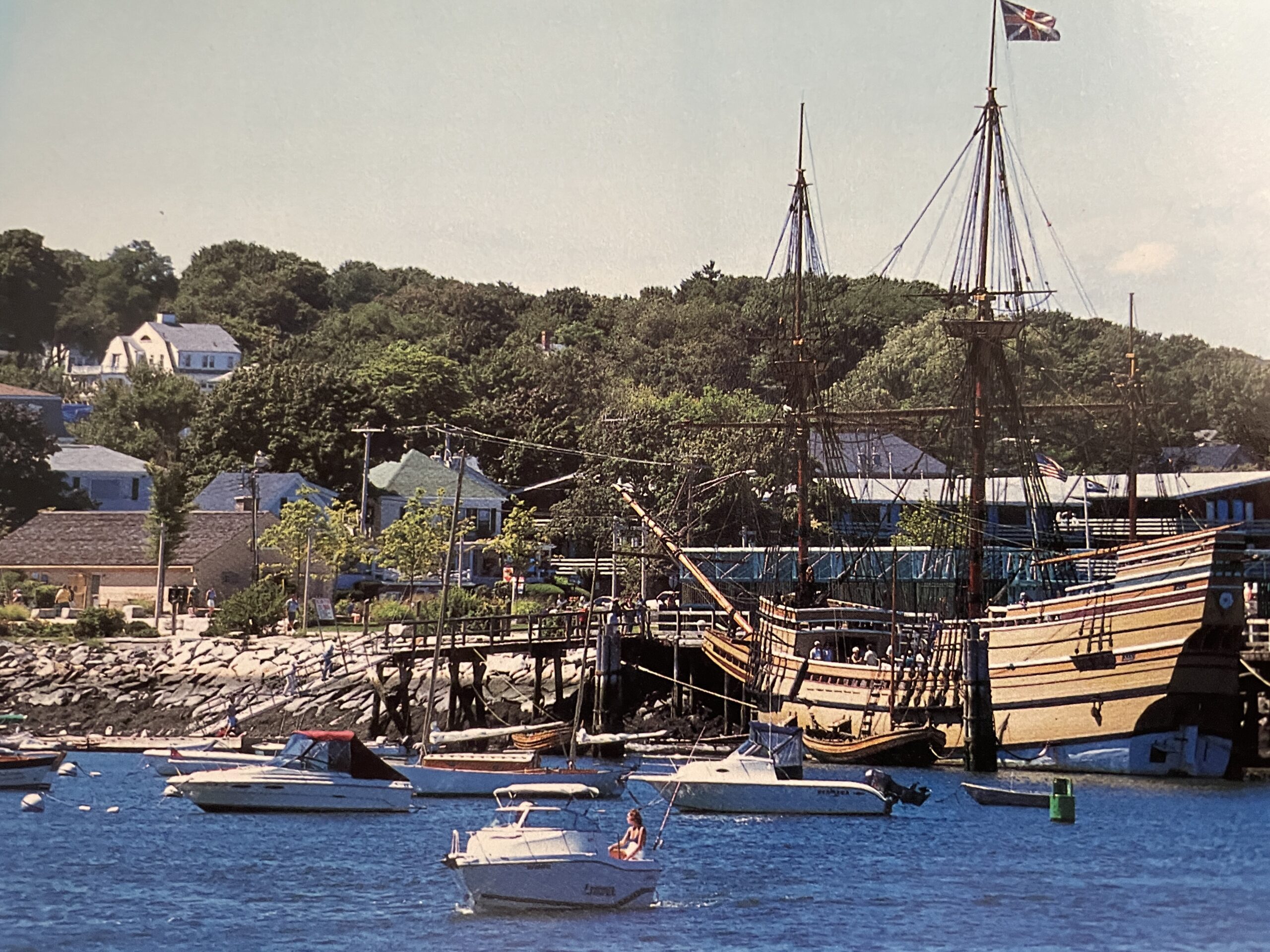

Plymouth first stirred my curiosity last November, when I came for the Thanksgiving festivities. My plan was to see the parade, visit Plymouth Rock, tour the Mayflower II—a replica of the original—and then head over to Plimoth Plantation, which is set up like the first settlement. But I got sidetracked as I walked toward the waterfront. Beneath me was a rolling brick sidewalk, and the street was lined with cozy, quaint seaside homes. It wasn’t what I’d expected. I guess I thought Plymouth would be, well, kind of cheesy, overrun by stores with names like Pilgrim Pete’s T-Shirt Palace and things of that sort. Instead, beautiful homes, antique shops and small bookstores filled the town. As I hurried to the parade, I thought about how I’d like to come back and explore.

When I returned to Plymouth this summer, I found a town that had gone through a serious warm-weather transformation. Crowds of people in T-shirts and shorts sauntered along the waterfront. Leaves filled the trees, the sky was a clear, warm blue, and those cozy houses now had big, colorful flowers blossoming in their gardens and flower pots. Plymouth was in full bloom.

My journey began at the town wharf—a popular spot with four large seafood restaurants and several excursion boats. At small booths, tickets were sold for whale-watching and harbor cruises, deep-sea fishing adventures and boat rides for kids. I listened as a couple of fishing buddies talked in the businesslike tone of a Wall Street deal with a boat captain about booking a trip. Meanwhile, the Lobster Excursion, a tour boat filled with children, passed by the wharf with the “Hokey-Pokey” blaring from its speakers.

It was low tide, and a beach appeared next to the sea wall. People walked along it while sandpipers hopped among the just-revealed stones looking for a meal. I skipped the beach and

meandered through a few of the requisite souvenir shops. One, Ye Olde Town Crier, had a sign in its window advertising hermit crabs. I walked in and saw dozens of tiny crabs hanging off the side of a tall cage, surrounded by throngs of fascinated kids begging their parents to buy some.

Then I saw the place mat—with the image of the Mayflower in Plymouth Harbor on a grizzly day as a small crew rowed to shore in a shallop. I stared at it for several minutes, soaking in the hostile surroundings and the difficult position those on the ship found themselves in. It made me realize how little I knew about the true Pilgrim story. I found some answers on the next block, across from Plymouth Rock, at the Plymouth Wax Museum.

The museum uses wax figures to tell the story of the Pilgrims by depicting different scenes from their history. The figures are incredibly lifelike, right down to their eyelashes and the creases in their faces.

There, I learned the people we know as the Pilgrims never called themselves that. They were the Scrooby Separatists, a group of religious dissidents from the village of Scrooby, England, who formed a church independent of the Church of England. With church and state being one and the same at the time, establishing an independent church was considered treasonous, and they were forced to flee the country to avoid being imprisoned.

The separatists traveled to the Netherlands, where they were free to practice their religion. But, as immigrants, they couldn’t get jobs that paid well, and they worried about losing their English traditions. So they traveled back to England and made plans to sail to the New World and settle at the northernmost boundary of the Virginia colony—the mouth of the Hudson River. In August 1620, the separatists, along with additional emigrants, set sail aboard two ships, the Mayflower and the Speedwell. But the Speedwell leaked badly, and the ships were forced to tum back twice. The Speedwell was eventually left behind, and the Mayflower sailed alone in September—much later than originally planned.

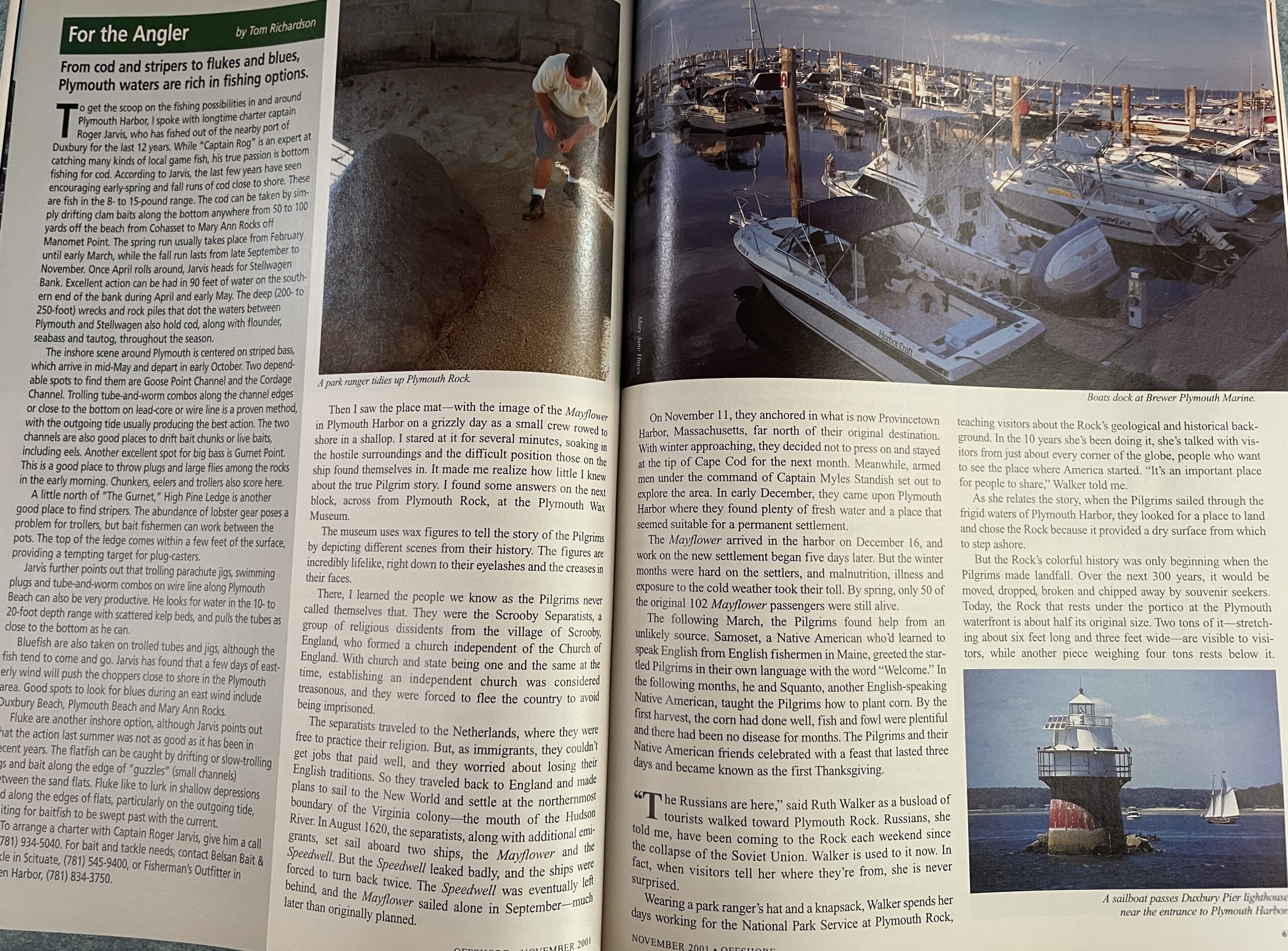

On November 11, they anchored in what is now Provincetown Harbor, Massachusetts, far north of their original destination. With winter approaching, they decided not to press on and stayed at the tip of Cape Cod for the next month. Meanwhile, armed men under the command of Captain Myles Standish set out to explore the area. In early December, they came upon Plymouth Harbor where they found plenty of fresh water and a place that seemed suitable for a permanent settlement.

The Mayflower arrived in the harbor on December 16, and work on the new settlement began five days later. But the winter months were hard on the settlers, and malnutrition, illness and exposure to the cold weather took their toll. By spring, only 50 of the original 102 Mayflower passengers were still alive.

The following March, the Pilgrims found help from an unlikely source. Samoset, a Native American who’d learned to speak English from English fishermen in Maine, greeted the startled Pilgrims in their own language with the word “Welcome.” In the following months, he and Squanto, another English-speaking Native American, taught the Pilgrims how to plant corn. By the first harvest, the corn had done well, fish and fowl were plentiful and there had been no disease for months. The Pilgrims and their Native American friends celebrated with a feast that lasted three days and became known as the first Thanksgiving.

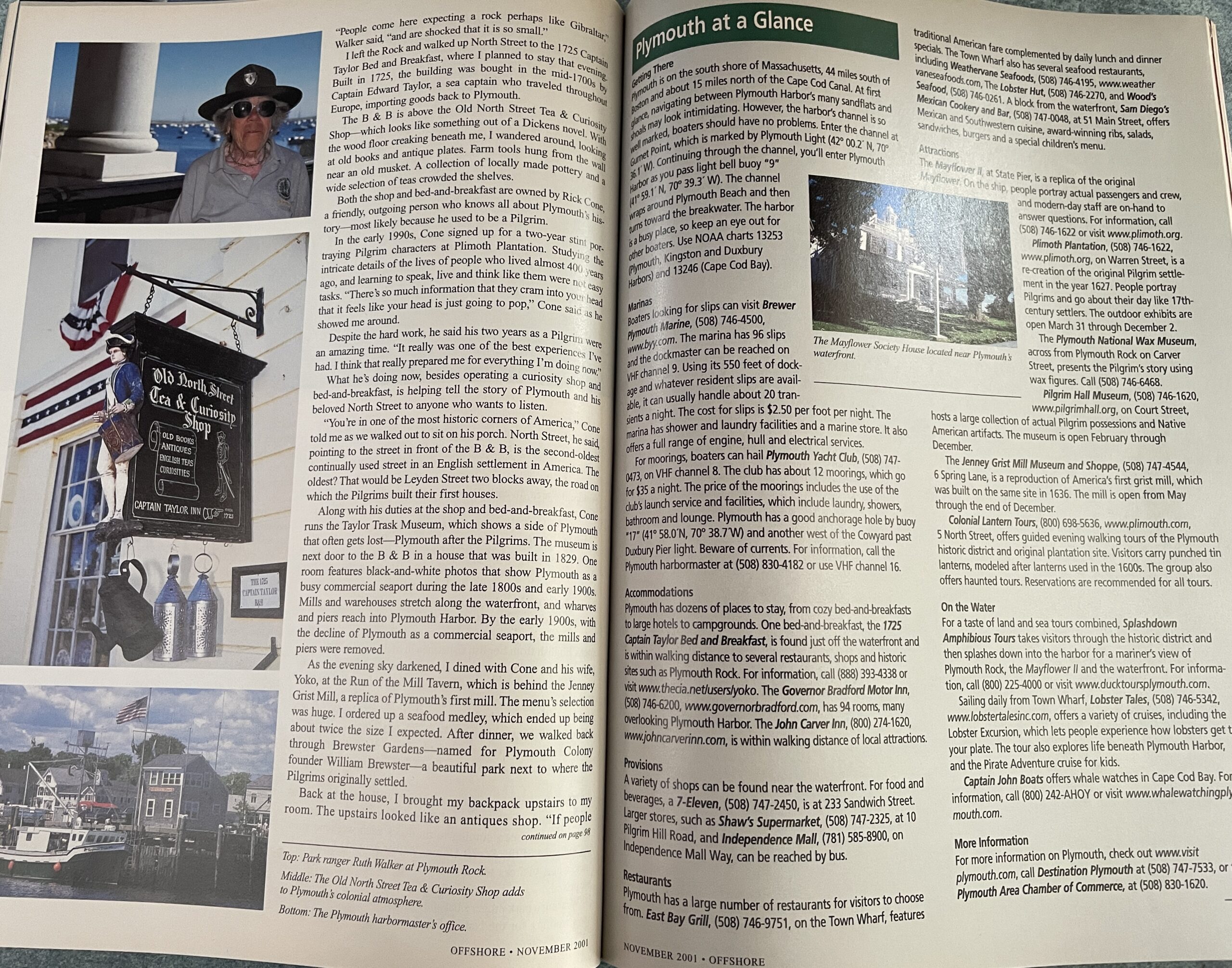

“The Russians are here,” said Ruth Walker as a busload of tourists walked toward Plymouth Rock. Russians, she told me, have been coming to the Rock each weekend since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Walker is used to it now. In fact, when visitors tell her where they’re from, she is never surprised.

Wearing a park ranger’s hat and a knapsack, Walker spends her days working for the National Park Service at Plymouth Rock, teaching visitors about the Rock’s geological and historical background. In the 10 years she’s been doing it, she’s talked with visitors from just about every corner of the globe, people who want to see the place where America started. “It’s an important place for people to share,” Walker told me.

As she relates the story, when the Pilgrims sailed through the frigid waters of Plymouth Harbor, they looked for a place to land and chose the Rock because it provided a dry surface from which to step ashore.

But the Rock’s colorful history was only beginning when the Pilgrims made landfall. Over the next 300 years, it would be moved, dropped, broken and chipped away by souvenir seekers. Today, the Rock that rests under the portico at the Plymouth waterfront is about half its original size. Two tons of it—stretching about six feet long and three feet wide—are visible to visitors, while another piece weighing four tons rests below it.

“People come here expecting a rock perhaps the size of Gibraltar,” Walker said, “and are shocked that it is so small.”

I left the Rock and walked up North Street to the 1725 Captain Taylor Bed and Breakfast, where I planned to stay that evening. Built in 1725, the building was bought in the mid-1700s by Captain Edward Taylor, a sea captain who traveled throughout Europe, importing goods back to Plymouth.

The B&B is above the Old North Street Tea & Curiosity Shop—which looks like something out of a Dickens novel. With the wood floor creaking beneath me, I wandered around, looking at old books and antique plates. Farm tools hung from the wall near an old musket. A collection of locally made pottery and a wide selection of teas crowded the shelves.

Both the shop and bed-and-breakfast are owned by Rick Cone, a friendly, outgoing person who knows all about Plymouth’s history—most likely because he used to be a Pilgrim.

In the early 1990s, Cone signed up for a two-year stint portraying Pilgrim characters at Plimoth Plantation. Studying the intricate details of the lives of people who lived almost 400 years ago, and learning to speak, live and think like them were not easy tasks. “There’s so much information that they cram into your head that it feels like your head is just going to pop,” Cone said as he showed me around.

Despite the hard work, he said his two years as a Pilgrim were an amazing time. “It really was one of the best experiences I’ve had. I think that really prepared me for everything I’m doing now.”

What he’s doing now, besides operating a curiosity shop and bed-and-breakfast, is helping tell the story of Plymouth and his beloved North Street to anyone who wants to listen.

“You’re in one of the most historic corners of America,” Cone told me as we walked out to sit on his porch. North Street, he said, pointing to the street in front of the B&B, is the second-oldest continually used street in an English settlement in America. The oldest? That would be Leyden Street two blocks away, the road on which the Pilgrims built their first houses.

Along with his duties at the shop and bed-and-breakfast, Cone runs the Taylor Trask Museum, which shows a side of Plymouth that often gets lost—Plymouth after the Pilgrims. The museum is next door to the B & B in a house that was built in 1829. One room features black-and-white photos that show Plymouth as a busy commercial seaport during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Mills and warehouses stretch along the waterfront, and wharves and piers reach into Plymouth Harbor. By the early 1900s, with the decline of Plymouth as a commercial seaport, the mills and piers were removed.

As the evening sky darkened, I dined with Cone and his wife, Yoko, at the Run of the Mill Tavern, which is behind the Jenney Grist Mill, a replica of Plymouth’s first mill. The menu’s selection was huge. I ordered up a seafood medley, which ended up being about twice the size I expected. After dinner, we walked back through Brewster Gardens—named for Plymouth Colony founder William Brewster—a beautiful park next to where the Pilgrims originally settled.

Back at the house, I brought my backpack upstairs to my room. The upstairs looked like an antiques shop. “If people want a modern place, they’re going to have to stay somewhere else. This is us.” Antique books filled shelves; likenesses of Daniel Webster and a rare print of Ralph Waldo Emerson hung on the wall. Cone cranked up and played an old Victrola to show it still worked. There was a 19th-century sailor’s cap, a harpoon, and a framed 1816 edition of the newspaper the Boston Patriot. Surrounded by these bits of history in a historic house in a historic town, I drifted off to sleep.

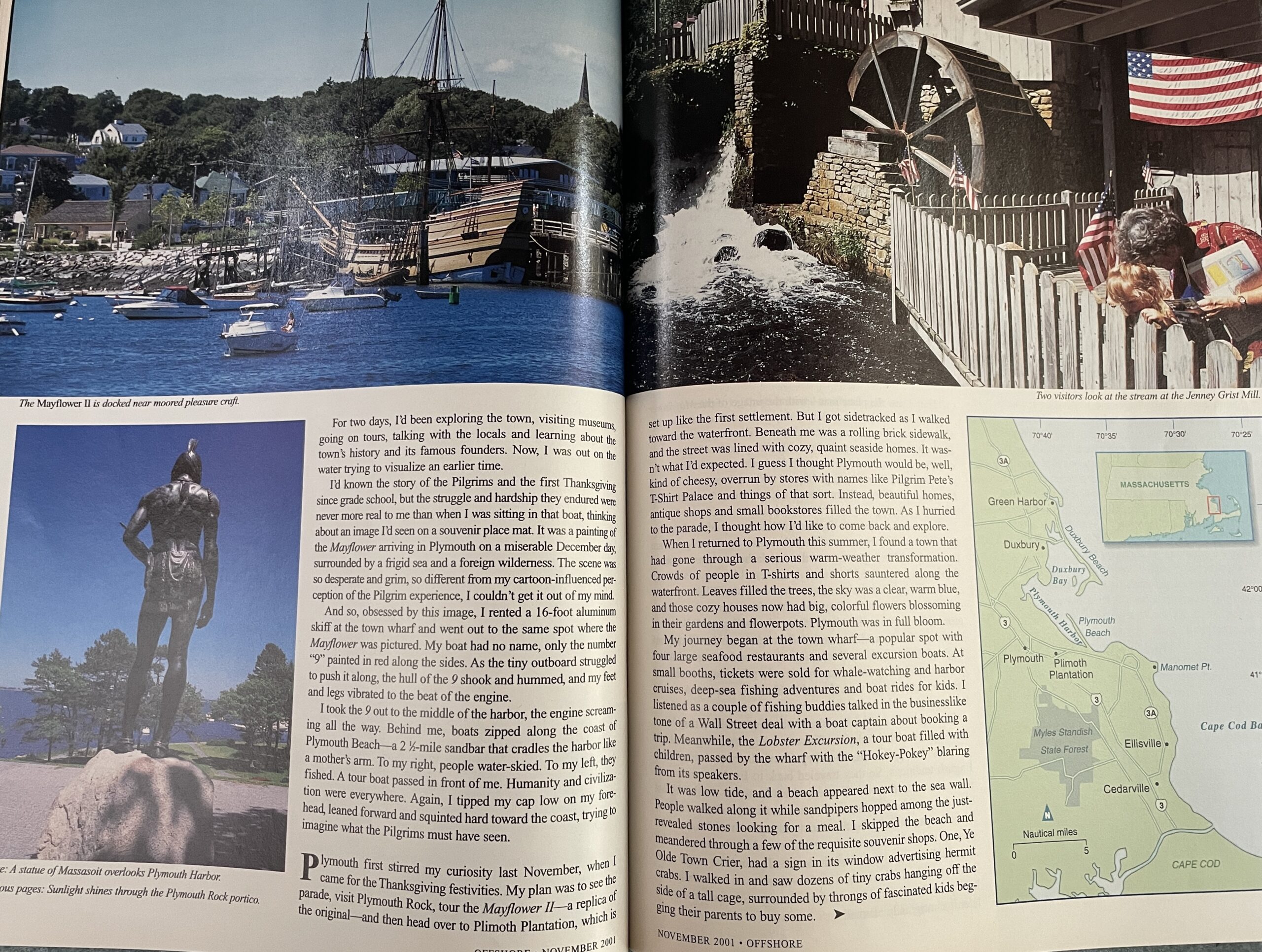

The next morning, I walked through Brewster Gardens on my way to the Jenney Grist Mill. Families with young children sat along the brook picnicking and feeding ducks. The wide, freshwater stream once provided water for the Pilgrims, and the original mill, built by John Jenney in 1636, allowed them to grind corn much faster than they could by hand. The replica, which is on the same site, is a working mill, and visitors can buy the mill’s ground corn in its gift shop.

Across from the mill, I found Jenney Pond—another beautiful park that connects to Brewster Gardens. I walked along a wooden bridge that spans the pond and watched as ducks and swans swam by, blue dragonflies buzzed the top of the water, and turtles sunned themselves on nearby branches. As I soaked in this serene, peaceful image of nature, I thought of how Plymouth had again surprised me.

From the pond, I made my way along a pedestrian path to Burial Hill, where people have been buried since the 1620s. Mayflower passengers William Brewster and the colony’s governor and historian, William Bradford, are buried there. Walking along the hill is like walking through time. I passed by a stone for Thomas Clarke, the mate on the Mayflower, who died in 1697 at the ripe old age of 98. Headstones mark the graves of Revolutionary War soldiers, Victorian men and women, and residents who died during the same time that World War I raged on. The last burial there was 1957.

Plymouth has more than its share of attractions that claim to be “America’s first” or “America’s oldest,” and my next destination—Pilgrim Hall Museum—was no exception. Built in 1824, it bills itself as the nation’s oldest continuously operated public museum. There, I saw artifacts that were likely used at the first Thanksgiving, including a cup made of wooden staves and a pewter plate. I looked at furniture brought over on the Mayflower, a bible and a wine cup owned by William Bradford, and a leather coat and swords belonging to well-known Pilgrims such as John Carver and Myles Standish. Seeing these things for myself was like seeing the Pilgrims in front of me. When I looked at Myles Standish’s sword, I felt a connection to Standish himself. The more I thought of it, the more I realized it is these connections that make Plymouth special. As I went from the Rock to the brook at Brewster Gardens to Leyden and North Streets, I walked over the same ground the Mayflower passengers walked on, and I felt I was sharing something directly with the Pilgrims. Again, my mind went back to the image on the souvenir place mat, and I felt compelled to get out on the water.

I walked back down to the waterfront, hopped in the 9 and went out into the harbor to take a good look at the coast. As Sea-Doos buzzed by me and tour boats passed, I tried to imagine how this was really the same coast I saw on that place mat. I tried to ignore the roaring boat engines, the shops, houses and radio towers, and I just stared at the coast. Eventually, I noticed the hills to the left, beyond the coast, and saw how they stretched along the waterfront. I focused on the trees that covered them, and the rim of the hills that ran against the skyline. All that was the same. All that was part of the Pilgrims’ Plymouth. From the blue skyline and tree-covered hills, I ran my eyes down to the water and looked behind me to see the sandbar wrapping around the harbor, and beyond that the trees of Clarks Island, where the Pilgrims stayed the night before they entered Plymouth. My eyes followed the water from the island, through the harbor, to where my boat drifted over tiny waves. The same waters and lands that surrounded the Pilgrims as they entered the harbor now surrounded me, and I felt connected to history.