South Shore Living

Water Country

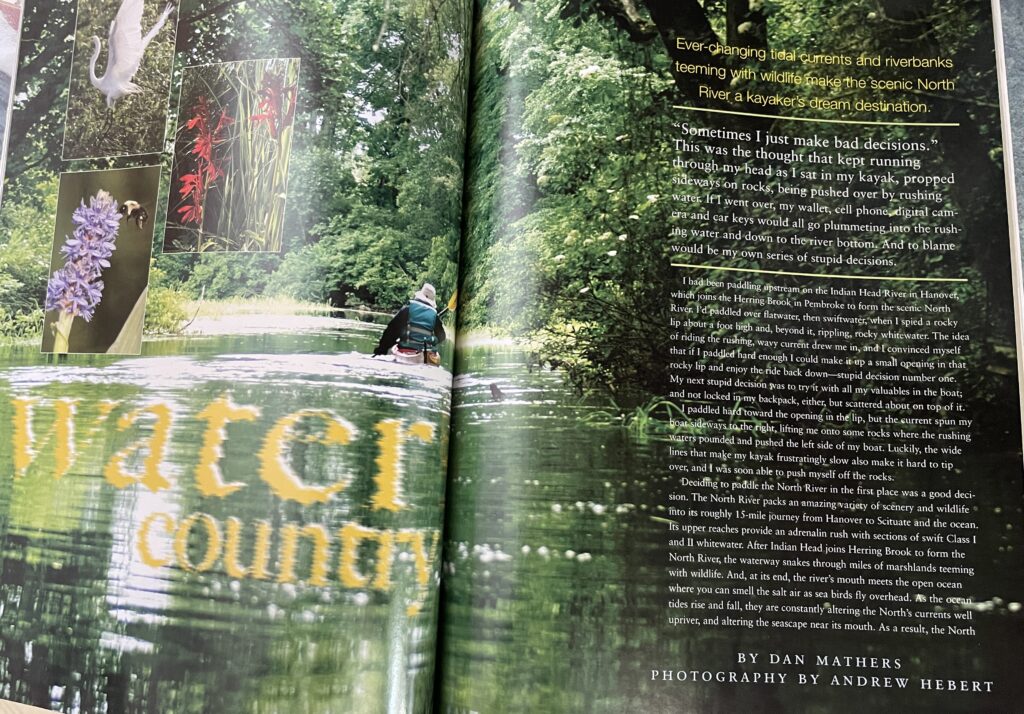

Ever-changing tidal currents and riverbanks teeming with wildlife make the scenic North River a kayaker’s dream destination.

(Text below)

“Sometimes I just make bad decisions.”

That thought kept running through my head as I sat in my kayak, propped sideways on rocks, being pushed over by rushing water. If I went over, my wallet, cell phone and car keys would all go plummeting into the rushing water and down to the river bottom. And to blame would be my own series of stupid decisions.

I had been paddling upstream on the Indian Head River in Hanover, Massachusetts — a narrow river that later joins with Herring Brook in Pembroke to form the scenic North River. I’d paddled over flatwater, then swiftwater, when I spied a rocky lip in the river about a foot high, and, beyond it, rippling, rocky whitewater. The idea of riding the rushing, wavy current drew me in, and I convinced myself that if I paddled hard enough I could make it up a small opening in that rocky lip and enjoy the ride back down — stupid decision Number One. My next stupid decision was to try it with all my valuables in the boat; and not locked in my backpack, either, but scattered about on top of it.

I paddled hard toward the opening in the lip, but the current spun my boat sideways to the right, lifting me onto some rocks where the rushing waters pounded and pushed the left side of my boat to where I was tipping hard to my right. Luckily, the wide lines that make my kayak frustratingly slow also make it hard to tip over. And I was soon able to push myself off the rocks after some tense moments and foul words.

Of course, I don’t always make bad decisions . . . no matter what my wife says. I sometimes make good ones, like deciding to paddle the North River in the first place. The North River packs an amazing variety of water, scenery and wildlife into its roughly 15-mile journey from Hanover to Scituate and the ocean. Its upper reaches provide an adrenalin rush with sections of swift Class I and II whitewater. After Indian Head joins Herring Brook to form the North River, the waterway snakes through miles of marshlands teeming with wildlife. And, at its end, the river’s mouth meets the open ocean where you can smell the salt air as sea birds fly overhead. As the ocean tides rise and fall, they are constantly altering the North’s currents well upriver, and altering the seascape near its mouth. As a result, the North doesn’t just change day to day, but hour to hour. It’s a river you can paddle a dozen times, and not have the same experience twice.

My plan was to explore the North River on two separate trips. On my first trip I’d explore the river’s upper reaches. And, on another trip, I’d explore its mouth. I started off by launching my boat in Hanover from a spot on Riverside Drive — a dead-end street with great access to the river and plenty of parking. I began by paddling up Indian Head River. I glided over smooth, black, flatwater, surrounded by dark green woodlands. Trees wrapped in leafy vines leaned over the water to create green archways above me. The water then became swift, and I soon saw the whitewater where I’d end up almost tipping.

After my rocky debacle, I turned around and headed downriver. Where Indian Head joins with Herring Brook, creating the North River, the river opens up into a large marshland called The Crotch. The river widens, and vast fields of reeds stretch out on both sides, with the tree-lined shores far in the distance.

I froze when I saw a tall, thin, white bird with a pointy bill standing beside the river. It was a Great Egret, and it too froze for a moment before taking a few steps away from the water and into the reeds, hoping I wouldn’t see him. As I watched him, a Great Blue Heron flew over the both of us, its graceful, monstrous long wings carrying it silently by. As I paddled on, I tried to give the Egret a wide berth, so as not to disturb it. But the skittish bird flew off, flapping like a pterodactyl with its sticklike legs stretched out behind it.

As I paddled out of The Crotch, the reeds faded away, and the river narrowed again. Along the shores were large houses with beautiful gardens and perfectly manicured lawns. While I prefer to get away from civilization when kayaking, this part of the river was like paddling through an issue of Home and Garden Magazine, and although it wasn’t wild, it was certainly scenic.

I passed under the Route 53 bridge, then under the Washington Street bridge immediately after it, where I got my first taste of the North River’s strong and ever-changing currents. To my left, the river appeared to be flowing upstream, to the right it flowed downstream, and in front of me a current flowed sideways to my left. When I returned this way a few hours later, the water appeared as calm as glass.

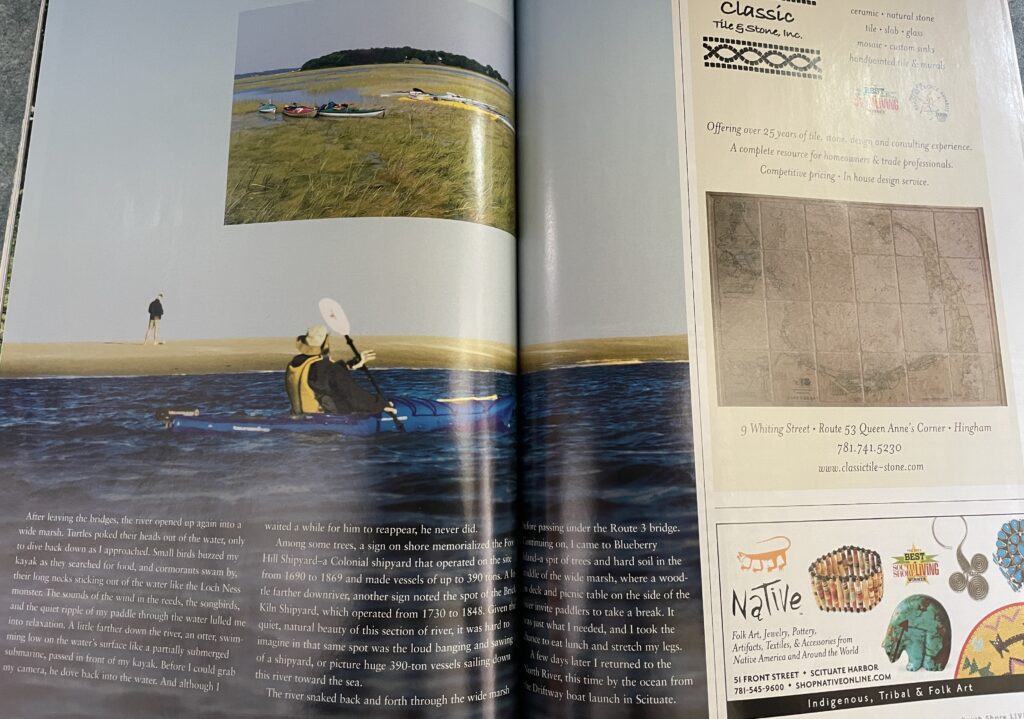

Smart boaters should do what I didn’t do before paddling this river — check the tides. (Tidal info is available on the North and South Rivers Watershed Association website at www.nsrwa.org.) After leaving the bridges, the river opened up again into a wide marsh. Turtles poked their heads out of the water, only to dive back down as I approached. Small birds buzzed my kayak as they searched for food, and cormorants swam by, their long necks sticking out of the water like the Loch Ness monster. The sounds of the wind in the reeds, the songbirds, and the quiet ripple of my paddle through the water lulled me into relaxation. Perhaps too much, because when a fish jumped out of the water next to my paddle, it scared me and I lurched violently to my right, almost tipping the kayak over, once again. A little farther down the river, an otter, swimming low on the water’s surface like a partially submerged submarine, passed in front of my kayak. Before I could grab my camera, he dove back into the water. And although I waited a while for him to reappear, he never did. I’d see two more otters that day . . . and not get a photo of a single one.

Among some trees, a sign on shore memorialized the Fox Hill Shipyard — a colonial shipyard that operated on the site from 1690 to 1869 and made vessels of up to 390 tons. A little farther downriver, another sign noted the spot of the Brick Kiln Shipyard, which operated from 1730 to 1848. Given the quiet, natural beauty of this section of river, it was hard to imagine in that same spot was the loud banging and sawing of a shipyard, or picture huge 390-ton vessels sailing down this river toward the sea.

The river snaked back and forth through the wide marsh before passing under the Route 3 bridge, where the highway’s decaying uprights looked like huge Roman columns standing out of the water. Continuing on, I came to Blueberry Island — a spit of trees and hard soil in the middle of the wide marsh, where a wooden deck and picnic table on the side of the river invite paddlers to take a break. It was just what I needed, and I took the chance to eat lunch and stretch my legs. After paddling on, I noticed thick clouds moving in from the west, and I wondered if the rain forecasted for that evening was making better time than I was. I decided it was best to turn back and take up exploring the river’s mouth at another time.

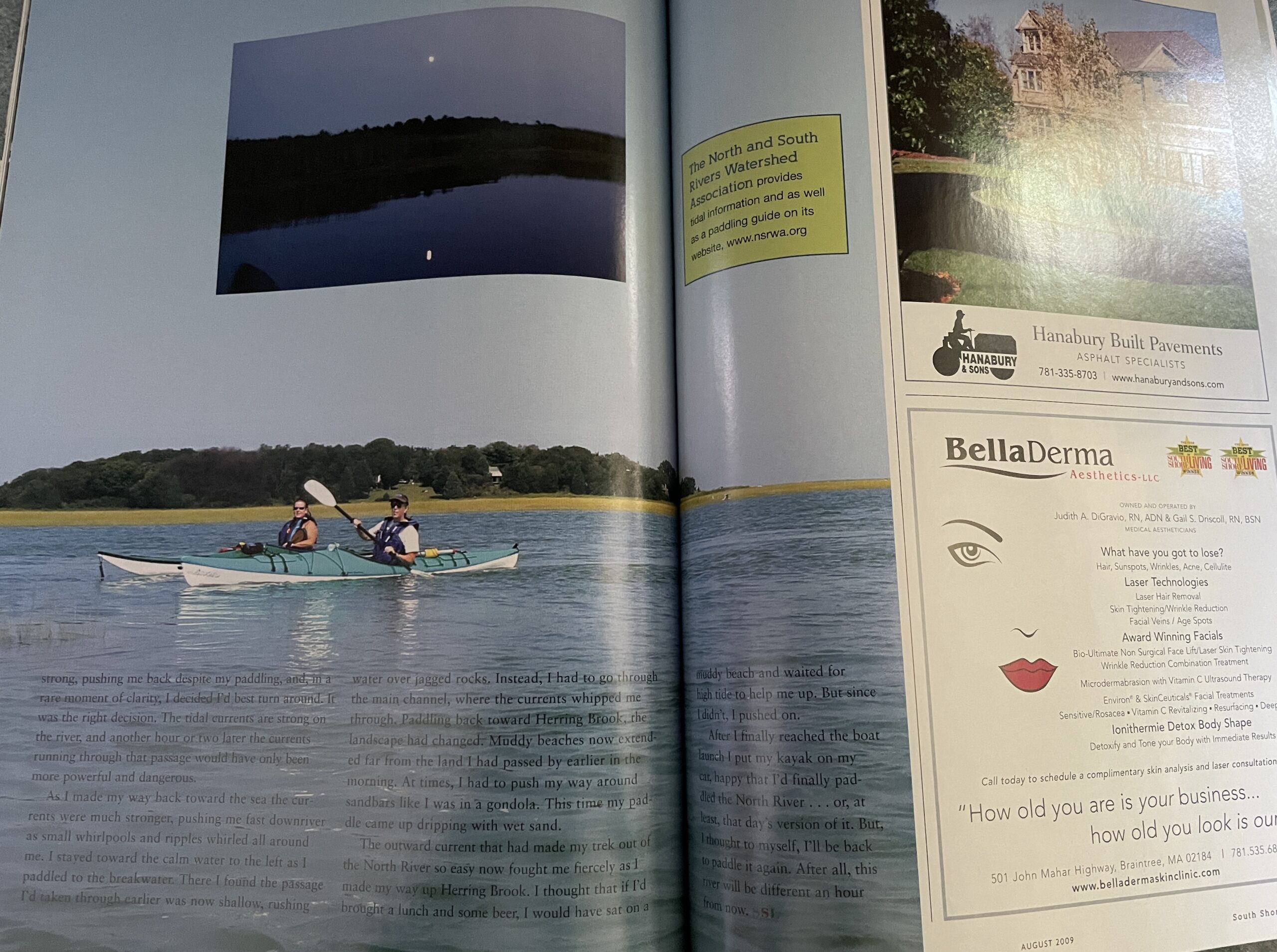

A few days later I returned to the North River, this time by the ocean from the Driftway boat launch in Scituate. It was roughly 5:30 in the morning, just after sunrise, but you never would have known it. The thick clouds overhead blocked out the rising sun. Being just after high tide, sea water flooded the normally grassy marsh near the boat launch, and a wide expanse of silver, mercurial water blended seamlessly with the ghostly mist and gray sky above it.

I paddled out, but I had a problem: I had no idea where to go. Near the mouth of the river, Herring Brook splits off to the north and runs right up to the Driftway boat launch. My map showed Herring Brook as an easily navigable narrow stream that ran down to the river. But high tide had covered all that dry land on my map in water, making it hard to see where to go or distinguish brook from river from ocean. To make matters worse, the fog hid distant shorelines and markers, making it difficult for me to get my bearings. Being great with decisions, I just set out into the gray distance, hoping Id find my way (and not have to call the Coast Guard).

As I paddled out not knowing where the deep water of the brook was, I passed over the grasslands where there was barely enough water to float my boat. Often, my paddle could only make it halfway into the water, and would come up dripping with wet grass. I rounded a beach with small cottages to my right and then paddled over to a breakwater, where a small red building was covered with buoys. When I checked my map, I found I was at the North’s mouth. I passed through a small opening in the breakwater and paddled into the river, where the mouth is marked by boats moored at the North River Marina and the Route 3A Bridge.

After passing under the bridge, the atmosphere seemed to dramatically change from sea to river. The air became thick and heavy. Mosquitoes appeared. And the wide expanse of the water narrowed into the river I’d been familiar with the other day. The river again snaked through marshlands, although this area had short grass like an unmowed lawn, whereas upriver the marshes were dominated by tall reeds.

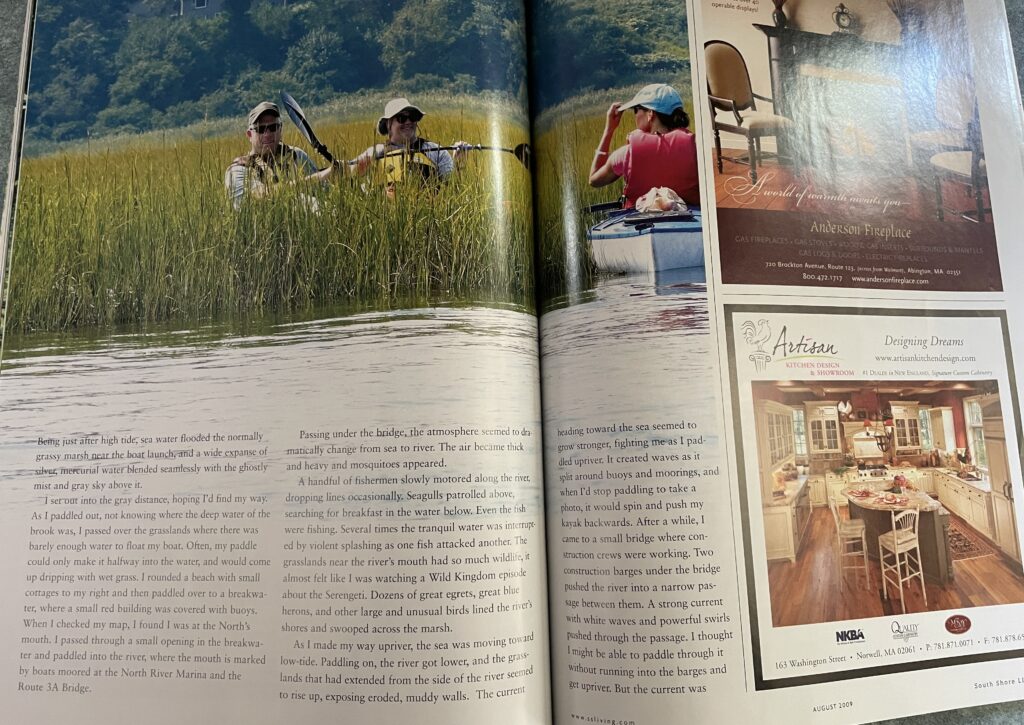

It seemed everyone was fishing. A handful of fishermen slowly motored along the river, dropping lines occasionally. Seagulls patrolled above, searching for breakfast in the water below. Even the fish were fishing. Several times the tranquil water was interrupted by violent splashing as one fish attacked another, and you could hear the whip-whip-whipping as a predator mauled its prey.

The grasslands near the river’s mouth had so much wildlife, it almost felt like I was watching a Wild Kingdom episode about the Serengeti. Dozens of Great Egrets, Great Blue Herons, and other large and unusual birds lined the river’s shores and swooped across the marsh. I regretted not knowing my birds as I watched so many fascinating feathered creatures all around me.

As I made my way upriver, the sea was moving toward low-tide. Paddling on, as the river got lower, the grasslands that had extended from the side of the river seemed to rise up, exposing eroded, muddy walls. First it was a foot high, then two, then more. And what had been a grassland I’d been paddling through soon took on the look of a muddy canyon. The current heading toward the sea seemed to grow stronger, fighting me as I paddled upriver. It created waves as it split around buoys and moorings, and when I’d stop paddling to take a photo, it would spin and push my kayak backwards. After a while, I came to a small bridge where construction crews were working. Two construction barges under the bridge pushed the river into a narrow passage between them. A strong current with white waves and powerful swirls pushed through the passage. I thought I might be able to paddle through it without running into the barges and get upriver. But the current was strong, pushing me back despite my paddling, and, in a rare moment of clarity, I decided I’d best turn around. It was the right decision. The tidal currents are strong on the river, and another hour or two later the currents running through that passage would have only been more powerful and dangerous.

As I made my way back toward the sea, the banks now stood a good four feet above the water, and the distinct stench of low-tide was setting in. Passing under the Route 3A bridge again, the currents were much stronger, pushing me fast downriver as small whirlpools and ripples whirled all around me. I stayed toward the calm water to the left as I paddled to the breakwater. There I found the passage I’d taken through earlier was now shallow, rushing water over jagged rocks. Instead, I had to go through the main channel, where the currents whipped me through.

Paddling back toward Herring Brook, the landscape had changed. Muddy beaches now extended far from the land I had passed by earlier in the morning. And instead of watching out for shallow grassy spots, I now had to watch out for sandbars. At times, I had to push my way around sandbars like I was in a gondola. My paddle again only submerged halfway, this time coming up dripping with wet sand.

When I reached Herring Brook, the muddy shore stood a good five feet out of the water, and I couldnt see any of the grassland above it. The outward current that had made my trek out of the North River so easy now fought me fiercely as I made my way up Herring Brook. I thought that if I’d brought a lunch and some beer, I would have sat on a muddy beach and waited for high tide to help me up. But since I didn’t, I pushed on.

After I finally reached the boat launch, I looked out to see a field of green grass and brown mud had replaced the gray, watery expanse from earlier that morning. I put my kayak on my car, happy that I’d finally paddled the North River . . . or, at least, that day’s version of it. But, I thought to myself, I’ll be back to paddle it again. After all, this river will be different an hour from now.